The Stream Control Transmission Protocol¶

The Stream Control Transmission Protocol (SCTP) RFC 4960 was defined in the late 1990s, early 2000s as an alternative to the Transmission Control Protocol. The initial design of SCTP was motivated by the need to efficiently support signaling protocols that are used in Voice over IP networks. These signaling protocols allow to create, control and terminate voice calls. They have different requirements than regular applications like email, http that are well served by TCP’s bytestream service.

One of the first motivations for SCTP was the need to efficiently support multihomed hosts, i.e. hosts equipped with two or more network interfaces. The Internet architecture and TCP in particular were not designed to handle efficiently such hosts. On the Internet, when a host is multihomed, it needs to use several IP addresses, one per interface. Consider for example a smartphone connected to both WiFi and 3G. The smartphone uses one IP address on its WiFi interface and a different one on its 3G interface. When it establishes a TCP connection through its WiFi interface, this connection is bound to the IP address of the WiFi interface and the segments corresponding to this connection must always be transmitted through the WiFi interface. If the WiFi interface is not anymore connected to the network (e.g. because the smartphone user moved), the TCP connection stops and need to be explicitly reestablished by the application over the 3G interface. SCTP was designed to support seamless failover from one interface to another during the lifetime of a connection. This is a major change compared to TCP [1].

A second motivation for designing SCTP was to provide a different service than TCP’s bytestream to the applications. A first service brought by SCTP is the ability exchange messages instead of only a stream of bytes. This is a major modification which has many benefits for applications. Unfortunately, there are many deployed applications that have been designed under the assumption of the bytestream service. Rewriting them to benefit from a message-mode service will require a lot of effort. It seems unlikely as of this writing to expect old applications to be rewritten to fully support SCTP and use it. However, some new applications are considering using SCTP instead of TCP. Voice over IP signaling protocols are a frequently cited example. The Real-Time Communication in Web-browsers working group is also considering the utilization of SCTP for some specific data channels [JLT2013]. From a service viewpoint, a second advantage of SCTP compared to TCP is its ability to support several simultaneous streams. Consider a web application that needs to retrieve five objects from a remote server. With TCP, one possibility is to open one TCP connection for each object, send a request over each connection and retrieve one object per connection. This is the solution used by HTTP/1.0 as explained earlier. The drawback of this approach is that the application needs to maintain several concurrent TCP connections. Another solution is possible with HTTP/1.1 [NGB+1997] . With HTTP/1.1, the client can use pipelining to send several HTTP Requests without waiting for the answer of each request. The server replies to these requests in sequence, one after the other. If the server replies to the requests in the sequence, this may lead to head-of-line blocking problems. Consider that the objects different sizes. The first object is a large 10 MBytes image while the other objects are small javascript files. In this case, delivering the objects in sequence will cause a very long delay for the javascript files since they will only be transmitted once the large image has been sent.

With SCTP, head-of-line blocking can be mitigated. SCTP can open a single connection and divide it in five logical streams so that the five objects are sent in parallel over the single connection. SCTP controls the transmission of the segments over the connection and ensures that the data is delivered efficiently to the application. In the example above, the small javascript files could be delivered as independent messages before the large image.

Another extension to SCTP RFC 3758 supports partially-reliable delivery. With this extension, an SCTP sender can be instructed to “expire” data based on one of several events, such as a timeout, the sender can signal the SCTP receiver to move on without waiting for the expired data. This partially reliable service could be useful to provide timed delivery for example. With this service, there is an upper limit on the time required to deliver a message to the receiver. If the transport layer cannot deliver the data within the specified delay, the data is discarded by the sender without causing any stall in the stream.

SCTP segments¶

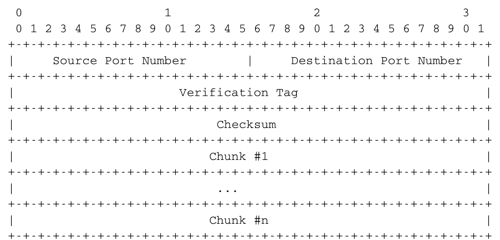

SCTP entities exchange segments. In contrast with TCP that uses a simple segment format with a limited space for the options, the designers of SCTP have learned from the experience of using and extending TCP during almost two decades. An SCTP segment is always composed of a fixed size common header followed by a variable number of chunks. The common header is 12 bytes long and contains four fields. The first two fields and the Source and Destination ports that allow to identify the SCTP connection. The Verification tag is a field that is set during connection establishment and placed in all segments exchanged during a connection to validate the received segments. The last field of the common header is a 32bits CRC. This CRC is computed over the entire segment (common header and all chunks). It is computed by the sender and verified by the receiver. Note that although this field is named Checksum RFC 4960 it is computed by using the CRC-32 algorithm that has much stronger error detection capabilities than the Internet checksum algorithm used by TCP [SGP98].

The SCTP segment format

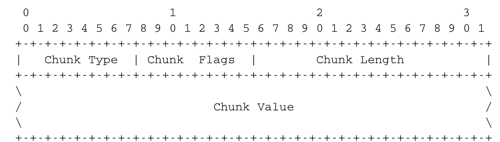

The SCTP chunks play a key role in the extensibility of SCTP. In TCP, the extensibility of the protocol is provided by the utilisation of options that allow to extend the TCP header. However, even with options the TCP header cannot be longer than 64 bytes. This severely restricts our ability to significantly extend TCP [RIB2013]. In SCTP, a segment, which must be transmitted inside a single network packet, like a TCP segment, can contain a variable number of chunks and each chunk has a variable length. The payload that contains the data provided by the user is itself a chunk. The SCTP chunks are a good example of a protocol format that can be easily extended. Each chunk is encoded as four fields shown in the figure below.

The SCTP chunk format

The first byte indicates the chunk type. 15 chunk types are defined in RFC 4960 and new ones can be easily added. The low-order 16 bits of the first word contain the length of the chunk in bytes. The presence of the length field ensures that any SCTP implementation will be able to correctly parse any received SCTP segment, even if it contains unknown or new chunks. To further ease the processing of unknown chunks, RFC 4960 uses the first two bits of the chunk type to specify how an SCTP implementation should react when receiving an unknown chunk. If the two high-order bits of the type of the unknown are set to 00, then the entire SCTP segment containing the chunk should be discarded. It is expected that all SCTP implementations are capable of recognizing and processing these chunks. If the first two bits of the chunk type are set to 01 the SCTP segment must be discarded and an error reported to the sender. If the two high order bits of the type are set to 10 (resp. 11), the chunk must be ignored, but the processing of the other chunks in the SCTP segment continues (resp. and an error is reported). The second byte contains flags that are used for some chunks.

Connection establishment¶

The SCTP protocol was designed shortly after the first Denial of Service attacks against the three-way handshake used by TCP. These attacks have heavily influenced the connection establishment mechanism chosen for SCTP. An SCTP connection is established by using a four-way handshake.

The SCTP connection establishment uses several chunks to specify the values of some parameters that are exchanged. The SCTP four-way handshake uses four segments as shown in the figure below.

The first segment contains the INIT chunk. To establish an SCTP connection with a server, the client first creates some local state for this connection. The most important parameter of the INIT chunk is the Initiation tag. This value is a random number that is used to identify the connection on the client host for its entire lifetime. This Initiation tag is placed as the Verification tag in all segments sent by the server. This is an important change compared to TCP where only the source and destination ports are used to identify a given connection. The INIT` chunk may also contain the other addresses owned by the client. The server responds by sending an INIT-ACK chunk. This chunk also contains an Initiation tag chosen by the server and a copy of the Initiation tag chosen by the client. The INIT and INIT-ACK chunks also contain an initial sequence number. A key difference between TCP’s three-way handshake and SCTP’s four-way handshake is that an SCTP server does not create any state when receiving an INIT chunk. For this, the server places inside the INIT-ACK reply a State cookie chunk. This State cookie is an opaque block of data that contains information computed from the INIT and INIT-ACK chunks that the server would have had stored locally, some lifetime information and a signature. The format of the State cookie is flexible and the server could in theory place almost any information inside this chunk. The only requirement is that the State cookie must be echoed back by the client to confirm the establishment of the connection. Upon reception of the COOKIE-ECHO chunk, the server verifies the signature of the State cookie. The client may provide some user data and an initial sequence number inside the COOKIE-ECHO chunk. The server then responds with a COOKIE-ACK chunk that acknowledges the COOKIE-ECHO chunk. The SCTP connection between the client and the server is now established. This four-way handshake is both more secure and more flexible than the three-way handshake used by TCP. The detailed formats of the INIT, INIT-ACK, COOKIE-ECHO and COOKIE-ACK chunks may be found in RFC 4960.

Reliable data transfert¶

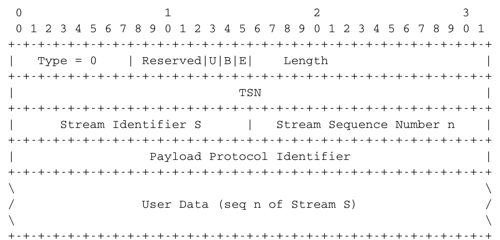

SCTP provides a slightly different service model RFC 3286. Once an SCTP connection has been established, the communicating hosts can access two or more message streams. A message stream is a stream of variable length messages. Each message is composed of an integer number of bytes. The connection-oriented service provided by SCTP preserves the message boundaries. It is interesting to analyze how SCTP provides the message-mode service and contrast SCTP with TCP. Data is exchanged by using data chunks. The format of these chunks is shown in the figure below.

The SCTP DATA chunk

An SCTP DATA chunk contains several fields as shown in the figure above. The detailed description of this chunk may be found in RFC 4960. For simplicity, we focus on an SCTP connection that supports a single stream. SCTP uses the Transmission Sequence Number (TSN) to sequence the data chunks that are sent. The TSN is also used to reorder the received DATA chunks and detect lost chunks. This TSN is encoded as a 32 bits field, as the sequence number by the TCP. However, the TSN is only incremented by one for each data chunk. This implies that the TSN space does not wrap as quickly as the TCP sequence number. When a small message needs to be sent, the SCTP entity creates a new data chunk with the next available TSN and places the data inside the chunk. A single SCTP segment may contain several data chunks, e.g. when small messages are transmitted. Each message is identified by its TSN and within a stream all messages are delivered in sequence. If the message to be transmitted is larger than the underlying network packet, SCTP needs to fragment the message in several chunks that are placed in subsequent segments. The packing of the message in successive segments must still enable the receiver to detect the message boundaries. This is achieved by using the B and E bits of the second high-order byte of the data chunk. The B (Begin) bit is set when the first byte of the User data field of the data chunk is the first byte of the message. The E (End) bit is set when the last byte of the User data field of the data chunk is the last byte of the message. A small message is always a sent as chunk whose B and E bits are set to 1. A message which is larger than one network packet will be fragmented in several chunks. Consider for example a message that needs to be divided in three chunks sent in three different SCTP segments. The first chunk will have its B bit set to 1 and its E bit set to 0 and a TSN (say x). The second chunk will have both its B and E bits set to 0 and its TSN will be x+1. The third, and last, chunk will have its B bit set to 0, its E bit set to 1 and its TSN will be x+2. All the chunks that correspond to a given message must have successive TSNs. The B and E bits allow the receiver to recover the message from the received data chunks.

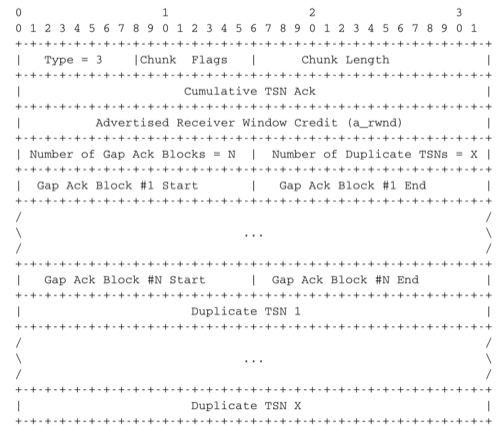

The data chunks are only one part of the reliable data transfert. To reliably transfer data, a transport protocol must also use acknowledgements, retransmissions and flow-control. In SCTP, all these mechanisms rely on the Selective Acknowledgements (Sack) chunk whose format is shown in the figure below.

The SCTP Sack chunk

This chunk is sent by a sender when it needs to send feedback about the reception of data chunks or its buffer space to the remote sender. The Cumulative TSN ack contains the TSN of the last data chunk that was received in sequence. This cumulative indicates which TSN has been reliably received by the receiver. The evolution of this field shows the progress of the reliable transmission. This is the first feedback provided by SCTP. Note that in SCTP the acknowledgements are at the chunk level and not at the byte level in contrast with TCP. While SCTP transfers messages divided in chunks, buffer space is still measured in bytes and not in variable-length messages or chunks. The Advertised Receiver Window Credit field of the Sack chunk provides the current receive window of the receiver. This window is measured in bytes and its left edge is the last byte of the last in-sequence data chunk.

The Sack chunk also provides information about the received out-of-sequence chunks (if any). The Sack chunk contains gap blocks that are in principle similar to the TCP Sack option. However, there are some differences between TCP and SCTP. The Sack option used by TCP has a limited size. This implies that if there are many gaps that need to be reported, a TCP receiver must decide which gaps to include in the SACK option. The SCTP Sack chunk is only limited by the network packet length, which is not a problem in practice. A second difference is that SCTP can also provide feedback about the reception of duplicate chunks. If several copies of the same data chunk have been received, this probably indicates a bad heuristic on the sender. The last part of the Sack chunk provides the list of duplicate TSN received to enable a sender to tune its retransmission mechanism based on this information. Some details on a possible use of this field may be found in RFC 3708. The last difference with the TCP SACK option is that the gaps are encoded as deltas relative to the Cumulative TSN ack. These deltas are encoded as 16 bits integers and allow to reduce the length of the chunk.

Connection release¶

SCTP uses a different approach to terminante connections. When an application requests a shutdown of a connection, SCTP performs a three-way handshake. This handshake uses the SHUTDOWN, SHUTDOWN-ACK and SHUTDOWN-COMPLETE chunks. The SHUTDOWN chunk is sent once all outgoing data has been acknowledged. It contains the last cumulative sequence number. Upon reception of a SHUTDOWN chunk, an SCTP entity informs its application that it cannot accept anymore data over this connection. It then ensures that all outstanding data have been delivered correctly. At that point, it sends a SHUTDOWN-ACK to confirm the reception of the SHUTDOWN segment. The three-way handshake completes with the transmission of the SHUTDOWN-COMPLETE chunk RFC 4960.

Note that in contrast with TCP’s four-way handshake, the utilisation of a three-way handshake to close an SCTP connection implies that the client (resp. server) may close the connection when the application at the other end has still some data to transmit. Upon reception of the SHUTDOWN chunk, an SCTP entity must stop accepting new data from the application, but it still needs to retransmit the unacknowledged data chunks (the SHUTDOWN chunk may be placed in the same segment as a Sack chunk that indicates gaps in the received chunks).

SCTP also provides the equivalent to TCP’s RST segment. The ABORT chunk can be used to refuse a connection, react to the reception of an invalid segment or immediately close a connection (e.g. due to lack of resources).

Footnotes

| [1] | Recently, the IETF approved the Multipath TCP extension RFC 6824 that allows TCP to efficiently support multihomed hosts. A detailed presentation of Multipath TCP is outside the scope of this document, but may be found in [RIB2013] and on http://www.multipath-tcp.org |

![msc {

client [label="", linecolour=black],

server [label="", linecolour=black];

client=>server [ label = "INIT, Itag=1234", arcskip="1" ];

server=>client [ label = "INIT-ACK,cookie,ITag=5678", arcskip="1"];

|||;

client=>server [ label = "COOKIE-ECHO, cookie, Vtag=5678", arcskip="1" ];

server=>client [ label = "COOKIE-ACK,VTag=1234", arcskip="1"];

|||;

}](../_images/mscgen-112b6066e3540d53e3a8002cae08be775971de94.png)

![msc {

client [label="", linecolour=black],

server [label="", linecolour=black];

client=>server [ label = "SHUTDOWN(TSN=last)", arcskip="1" ];

server=>client [ label = "SHUTDOWN-ACK", arcskip="1"];

|||;

client=>server [ label = "SHUTDOWN-COMPLETE", arcskip="1" ];

|||;

}](../_images/mscgen-210e896458f611ed3bfa6317aa9397cfbaf2d15a.png)